Beyond the Former Middle East: Aesthetics, Civil Society, and the Politics of Representation

01 June 2011

‘There exists a specific sensory experience – the aesthetic – that holds the promise of both a new world of Art and a new life for individuals and the community.'[1]

–Jacques Rancière

I

A slap. An act of violence visited upon an individual that proved to have an afterlife that exceeded anything imaginable in the moment it was both delivered and received. On the morning of 17 December 2010, Mohamed Bouazizi, an unemployed Tunisian residing in Sidi Bouzid, a small town south of Tunis, was attempting to make ends meet by selling vegetables from a cart when, at 10.30am, he was harassed, slapped in the face by a municipal official, had his wares and scales confiscated and, upon complaining to the local governor’s office, was denied a fair hearing to air his grievances. These are the known facts of the matter according to eye-witnesses but it is what happened next that would give rise to an unprecedented revolution throughout the Middle East: at 11.30am, almost one hour after being harassed and slapped in the face, Mohamed Bouazizi purchased a can of gasoline (or possibly paint thinner), doused himself with it in front of the governor’s office, and set himself alight. These are the brute facts of the matter: a slap translates into an unforgiving act of self-immolation and thereafter into a conflagration that has brought with it both unforeseen freedoms and brutal repression in equal measure.

A slap. How did a relatively innocuous, but nonetheless humiliating, slap escalate into an act of self-immolation and thereafter into a series of region-wide conflicts? Admittedly, I pose this question without offering much hope of answering it; nevertheless, we might get closer to an answer if we enquire into what was contained in that slap in the first place and what forms of personal misery, social abjection and political abasement resided in this act of violence. Within this slap, at its irrevocable core and key to its combustive effect, we find both ignominy and despair; we find the desperation of a man who opts to sell vegetables on a street (which is not in itself an undignified trade if you were allowed to go about it unmolested); we witness the poverty and impoverishment of a whole generation of people cowed by despotism; we can perceive in this slap the totalitarian presence of Tunisia’s one-time president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali (along with his avaricious family and treacherous flunkies); and we can observe the thorny issue of gender (a woman slapping a younger man in public as if he were a child).[2] If we were to examine this slap more closely, we could also see the undoubted contempt for the rights of an individual under a despotic order – a contempt that is insidious insofar as it makes everyone an accomplice in the degradation of others; we could likewise detect evidence of the ill-gotten, ill-placed and ultimately illegitimate administration of power. There is, moreover, ample proof of a poverty of spirit and lack of empathy on the aggressor’s behalf (a totalitarian regime diminishes not only the brutalized but, perhaps just as pertinently, the brutalizers too). And there is in this slap, ultimately, the all too obvious manifestation of the years of malaise that had gripped an entire nation of people who had appeared to have resigned themselves to lives half lived. All that, and more, resided in this slap and it was this that culminated in an act of self-immolation that has in turn ignited an entire region.

There were two widely seen photographs of Mohamed Bouazizi circulated by the media after his self-immolation – three if we count the less well known one of him engulfed in flames as he stumbled blindly along the road outside the governor’s office. The first photograph showed him – or at least gave an outline of his form – bandaged head-to-toe, post-immolation and lying prostrate in a hospital bed in the Ben Arous-based Burn and Trauma Centre. He had garnered the full attention of officialdom by then, complete with a seemingly penitent and soon-to-be ousted Ben Ali at his bedside. Bouazizi is surrounded by doctors and nurses and possibly impervious to their presence – it is difficult to say as we cannot behold his charred face nor his unseeing eyes. The second photograph circulated shows Mohamed Bouazizi in more promising times. He is smiling against a red backdrop, possibly a carpet hung on a wall, and is mid-clap, his two hands just about to join one another in what is often seen as a universal expression of joy – or, indeed, warning. It is possible, of course, that the warning was there all along: a clap would eventually become – under the everyday conditions of totalitarianism and injustice – a slap. And that slap would thereafter realign not only the social and political constellations of the Middle East but the expectations surrounding the region and what constituted its aspirations and hopes for the future. Promise turns to admonition and the perdition of despair only to return to a promise again. Bouazizi’s self-immolation, whilst in itself an act of profound, irremediable disconsolation, has given rise to the promise of change throughout a region; despair has turned to hope, the very hope that he himself had fatally forsaken.

It would of course be desirable to think that a new order – an Arab Spring, if you like – can emerge in the coming years out of the events that are unfolding in the Middle East as I write, but history – the uneven, unpredictable, unforeseeable order of event following event – may have other ideas. To paraphrase Stephen Dedalus’s musings in Ulysses, history may yet still turn out to be the nightmare from which we are trying to awake. It is nevertheless true that perceptions have changed throughout the region and what is doable, sayable and thinkable in this context has been profoundly reconfigured if not irrevocably recalibrated. A promise of something else and the realignment of the socio-political horizons of possibility to which people aspire has been effected, so much so that further repression seems to merely steel the resolve of those calling for change throughout the region. The Arab malaise, so expertly dissected by writers such as Samir Kassir, which has lain so heavily on countries such as Tunisia and Egypt, to name but two, has been lifted and the promise of a future free from tyranny has been uttered.[3]

But what is the future of that promise; where does it go from here; where will it be sustained and what other act of violence will be visited upon it? Perhaps those are the real questions: what is the future of the promise we are currently witnessing in the Middle East and North Africa under the conditions of continued repression?

II

It may seem inopportune or even insensitive to talk about culture during a time when people are being murdered in the streets by the apparatuses of totalitarian states and demented despots. However, I would suggest that this is precisely the time to talk about culture; in fact, there is perhaps no better time to talk about culture than now. Although writing in a different context, the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 to be precise, Raymond W. Baker has convincingly argued that the looting of museums and the burning of libraries in Baghdad and elsewhere was not an inevitable after-effect of military incompetence and negligence (which would at least offer a degree of mitigation by dint of sheer idiocy), but the inevitable effect of policies that actively disregarded the imperative of protecting cultural landmarks in favour of base economic motives and short-term strategic advantage.[4] Although a list of 20 key sites in need of immediate protection was drawn up in advance of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, with the National Museum being first on the list, the only one that received such protection was the Ministry of Oil. This bias towards strategic short-termism left a country denuded of the very artefacts and cultural objects that would be needed to give any nation a coherent – albeit contested – sense of individual belonging and communality; the very sense of communality that generates both forms of historical consciousness and social cohesion. History, in sum, needs culture. And culture in Iraq, from its looted museums, burned libraries and the willful, invariably unprosecuted murders of intellectuals and academics, was effectively annihilated.[5]

A country deprived of culture exists in an ahistorical vacuum. With no sense of ontology, a degree of insight into where we are coming from and the nature of our being as a result, there can be no teleology; no development towards an end, whatever the latter may consist of in the long term. Without culture, people are at best unmoored from the very co-ordinates of history needed to produce a coherent narrative, be it social or political, in the present and, crucially, the future. It is this knowledge that no doubt drove protestors and soldiers alike to successfully protect the Egyptian Museum in Cairo when it came under attack from looters earlier this year. Similar acts of cultural defence were witnessed throughout Tunis following the popular uprisings in the wake of 17 December 2010. The culture contained within both the National Museum and the Egyptian Museum was indeed shared. It gave narrative and substance to a sense of belonging and would have, in the case of Iraq, greatly contributed to the rebuilding of a nation state that currently seems ill-prepared and unable to curtail and go beyond the internecine warfare and strife that continues to afflict it. Minus culture, that rebuilding, that sense of national cohesion, that sense that there may indeed be a long term common purpose, is not only all the more difficult to attain but most likely irretrievable.

How then are we to understand contemporary visual culture within the context of civil war and political unrest? To ask such a question is to engage both a plethora of possibilities and to coextensively descend into a veritable rabbit-hole of diminishing interpretive returns. Firstly, if visual culture is reducible to commentary on recent events, it risks becoming both reportage and agitprop; its aesthetic momentum and impact ultimately given over to and usurped by rhetoric and inevitably elided by self-righteousness. Why should visual culture respond to the immediacy of events and why should we want it to? I would suggest that such expectations are in danger of missing a fundamental point: visual culture, in all its aesthetic availability and ability to realign ways of seeing and our understanding of the world and our place in it, is always already political.

This is to observe that there has been a disconnect in recent years between aesthetics and politics whereby art was invariably seen as political only if it addressed politics in an overt fashion, whether it be in relation to forms of inequality, the mistreatment of individuals by the state, miscarriages of justice, the various wars and clandestine operations carried out in the name of the people (whoever they may be), and the seemingly never-ending ‘war on terror’. In order for any aesthetic proposition to maintain an urgency and ability to reconfigure ways of thinking and seeing, and thereafter engage if not challenge any politically motivated order of looking and understanding, it must, somewhat paradoxically, avoid being reduced to the category of the political. This onus, inasmuch as it speaks to artists, carries with it an imperative that curators, writers and art institutions in general would do well to observe. If history has imparted anything to us, and the history of art in particular, it is that politically sanctioned or censored art can only ever result in the banalities of agitprop.[6]

In what remains of this essay, I want to propose that visual culture contains an inherent aesthetic imperative and promise that cannot be reduced to either political posturing or the seemingly abstract qualities of formal arrangements. The aesthetics of visual culture, to use Jacques Rancière’s phrase, can reframe the ‘distribution of the sensible’ – that which can be seen, said or heard in any given milieu – and thereafter re-contextualize both material and symbolic space; or, simply put, insofar as it determines the way in which we see the world, the aesthetic subsequently plays a significant part in defining our place within it. For Rancière, artistic practices, to the extent that they participate in the socio-political and cultural realm, ‘take part in the partition of the perceptible insofar as they suspend the ordinary coordinates of sensory experience and reframe the network of relationships between spaces and times, subjects and objects, the common and the singular’.[7]

If we can agree that perception defines forms of participation in – not to mention the relationships formedwithin – social orders, then it is less problematic to accept that those modes and means of perception can also define and thereafter predicate who is included and, more critically, who is excluded from participating in political and social orders.[8]

III

Culture and its institutions involve forms of social participation. In these moments of engagement, aesthetics can open up a space for plurality and difference – not to mention dissensus and disagreement – to emerge.[9]

Aesthetics and visual culture can thereafter invite not only forms of civic participation but equally anticipate the very space needed for such forms of engagement to be effected. The aesthetic order in which culture exists is essential, I want to suggest here, to understanding notions such as engagement and the role of civic society in promoting equality and justice. This is one of the key lessons of Rancière: politics and aesthetics are indelibly imbricated; they are both engaged in defining if not contesting the realm of the sensible (that which can be seen, said and heard) and they are both about either policing or indeed provoking what and, crucially, who can be seen, said and heard.[10] Thereafter, politics and aesthetics can determine who is included and who is excluded in any given ‘distribution of the sensible’; who is the subject of equality and who is abandoned to the realm of non-representation.

There is perhaps a need here to be overt when discussing the show accompanying this catalogue: none of the works in The Future of a Promise, to be clear, can change the social conditions or political correlates of the Middle East. On their own, however, they can offer individual commentary and a prism through which to re-articulate the realities of a complex and increasingly divergent region and encourage the participation of people in the civic order of discussion and dialogue. Culture, in the form of shows such as The Future of a Promise, encourages the production and exchange of knowledge, some of which will inevitably challenge the partitioning and distribution of meaning (and social relations) in societies through the region – that much is a given.[11]

This is to further observe the extent to which art as a practice asks key questions about modes and means of representation, history, orders of knowledge and their retrieval, the impact of conflict on culture, the role audiences play in the production of meaning, the development of civic society and the uses of public space, and the institutional contexts within which such questions can be addressed. Which in turn begs the question as to what part, and to what degree, culture will play in the formation of civic society – not to mention the sphere of the political – in countries where dissent can result in imprisonment or worse.

The politics of visual culture in the Middle East, albeit to different degrees depending upon each country, has always been involved in a politics of representation and thereafter treated with a general level of suspicion if not downright hostility.[12] Which returns us to the question of how culture – the aesthetics of contemporary art practice – operates within and as part of the socio-political and historical moment of its production, dissemination and reception, nowhere more so than when inequality would appear to be the predicate as opposed to the exception to the rule of law and order. Before this question can be fully answered, it is important to note that aesthetics, visual culture in particular, does not promote equality – to suggest it does is to merely instrumentalize culture; rather, the aesthetics of visual culture promotes ways of thinking and seeing that realigns the distribution of the sensible order and thereafter an individual’s relationship to a socio-political order – and that can, indeed, lead to equality or a redistribution of roles and modes of participation within that order. Again, perhaps this is why culture, the agency and potential of the aesthetic, is only tolerated in parts of the Middle East – including the UAE and the very countries undergoing conflagration as I write – in a self-contained and heavily-censored version or, indeed, when it is safely repackaged in various outposts of Western institutions for the purpose of giving the privileged few a frisson of engagement but not the material substance of adequate political representation.[13]

The key question here is therefore concerned with a singular enquiry: what role will culture play in the Middle East – alongside the social and political realignment of Arab societies – in the development of civic society and the institutions of democracy, whatever the latter may mean in the context of predominantly Muslim countries.[14]

Commonly used to refer to the social and voluntary institutions that underwrite communities and social orders, as opposed to government interventions or commercially-driven initiatives, the formation of civic society in the Middle East is a key if not the key issue being addressed on the streets and in the squares of cities across the region. Instances of organizations that promote and uphold civil society include academia, activist groups, community foundations and organizations, cultural and environmental groups, and voluntary associations working with so-called disadvantaged communities – the very groups that are conspicuous in their absence across large swathes of the Middle East. Visual culture, in its bringing together of individuals in the form of a given, albeit elusive, community, is very much part of the development of civil society; it is likewise a combative and on occasion antagonistic force. It would be worth reiterating the number of artists exiled, shows shut down, and artworks censored in recent years in the Middle East – not to mention the relative neglect of cultural institutions across the region and the arbitrary religious edicts issued on the subject of representation – but it would be a litany that perhaps misses the point: culture, in its expression of a specific milieu and ways of thinking, seeing and doing, effectively realigns the order of politics and the horizon of social and political potential if not promise. Despots and self-styled rulers are therefore right to fear expressions of culture as they do those other bugbears of totalitarianism: education and research, both of which we find as cornerstones to any progressive cultural institution.

IV

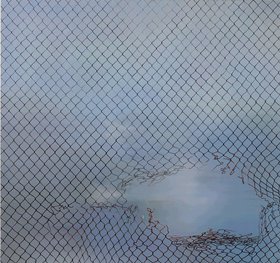

There is an elusive image in The Future of a Promise, a painting of wire fencing by Driss Ouadahi that is both imminently abstract and yet abstractly imminent; by which I mean, a reading of this image could focus on its painterly abstraction – recalling, for example, the grid-like monochromes of Frank Stella or Ad Reinhardt – or the literal imminence of wire fencing and its primary function: to keep people out of an area or contained within a certain boundary. We could, of course, go for both readings: this painting, steeped as it is in the history of painting – from minimalism to the geometric abstraction of traditional Islamic painting – is also about the architecture of control and restriction. In bringing to bear the history of painting on the subject of confinement and perhaps internment, if not imprisonment, Fences, Hole 2 (2011), questions any easy reading of the image or appropriation of it. In the context of the various conflicts in the Middle East, the topic of internment would have an undoubted resonance and Ouadahi’s work is, in this context, a painting that engages a global art tradition, conjoining both Western and Islamic modes of expression, that in turn brings the aesthetic – a distribution of the sensible – to bear upon the issues of land and statehood. If, however, we reduce this image to just that reading (internment, imprisonment and confinement), we risk ignoring its obvious aesthetic engagement with broader cultural forms and the history of art. For some, the fact that this painting can bring together Western styles of minimalism and Islamic geometric abstraction could be seen as political in and of itself insofar as it disavows any binaristic reading of cultural production within and beyond the region. Painting, the history of art, confinement, restriction, all come together here in a debate about the politics of aesthetics.

A bridge, fashioned as a flying carpet, traverses a room, hanging slightly above the viewer. In its three-dimensionality, it holds out a significant degree of aspiration and perhaps transcendence. Where does Nadia Kaabi-Linke’s Flying Carpets (2011) emerge from and where is it going? Is there an invitation to take on a journey in this work, a transaction inherent in the promise of the aesthetic to effect a community – no matter how elusive – of viewers or participants? A bridge is, after all, a point of conjunction and transformation, a leaving behind of one state or location in acceptance and anticipation of another. However, Kaabi-Linke’s bridge is also a reference to Il Ponte del Sepolcro in Venice where traders, legal and illegal, precariously trade their wares with the tourists who flock to the city every year. The so-called real world and the world of the aesthetic conjoin here in an object that is a metaphor for change.

Kaabi-Linke’s Flying Carpets also maintains and develops a minimalist tradition that speaks to the concept of trans-location, another concept that has particular purchase in the context of the Middle East and its diasporic hinterlands. We find a similar aesthetic at work in Ayman Yossri Daydban’s 1967/1948 Flag (2010), which consists of a metal sheet – which appears to have undergone an amateur bout of panel-beating – folded into a make-shift Palestinian flag. The flag looks disheveled and crumpled, if not forlorn – a metaphor, perhaps, for the seemingly permanent and forsaken state-of-exception that is Palestine today. And yet, this work, like all artistic production, is also involved in the continuum of art history, the legacy of minimalism and conceptualism in particular, that brings a discussion of aesthetics to bear on the politics and inequities of statehood, the praxis of minimalism, and the science of vexillology. The politics of statehood and the lack thereof are also the subject of Emily Jacir’s embrace (2005), which reveals an object – a conveyor belt for luggage – familiar to anyone with access to an airport, and yet coextensively renders it uncanny in its circular form. It is this circularity and inevitable return that reveals a bitter aside upon the purgatorial state of existence – minus, that is to note, the right of return – for many exiled Palestinians.

Flags return in Mounir Fatmi’s The Lost Springs (2011), which displays 22 unfurled flags with two of them – Tunisia and Egypt – supported not by flagpoles, as we might expect, but brooms. Fatmi’s overt comment on the sweeping out of the old, with the use of an actual broom, gives way to the possibility of more brooms being added to the piece over time. This work, far from looking to the past, attempts to anticipate the future and – given that it is open to adaptation and accrual in time – goes some way to challenging preconceptions about a static Middle East mired in the malaise and neglect of the past.[15]

Ayman Baalbaki’s painting of keffiyeh-clad youth also goes some way to engaging precisely the sense that certain symbols, in their abstract and aesthetic impact, cannot but challenge orders of seeing and thinking. The keffiyeh is a traditional cotton scarf worn by many who journey to or live in the Middle East. Its practicality has been long attested to as a protector from sun and sand when travelling in the desert and arid regions. It has been worn by Yemenite Jews and other Semitic people since biblical times; it has become the national symbol of Palestine (carefully nurtured by Yasser Arafat); it was adopted by Lawrence of Arabia and Erwin Rommel; it has been associated with Leila Khaled (during her time with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine); and donned by protesting youths from Paris to Tahrir Square and, more recently, adapted by American and Coalition forces stationed in the region. However, and from within our contemporary consensus in respect of the Middle East, it has been deemed an item promoting support for terrorism.[16] Baalbaki’s painting undoubtedly plays upon all of these meanings conterminously and again address how aesthetics and politics – brought together here in an item of clothing – are indelibly imbricated.

Baalbaki’s Al Maw3oud (2011), also plays to and exposes the durability of racist tropes that continue to define views of the Middle East and we daily witness, in reactions to the keffiyeh for example, the openly racist and derogatory images – the callous Arab, for example, or the militant driven by so-called radical Islamic ideals – that continue to predetermine representations of the region. Such tropes have a pedigree of sorts and can be found in Orientalist paintings from at least the eighteenth century onwards. Based on an 1821 play by Lord Byron, Eugène Delacroix’s apparently instructive Death of Sardanapalus (1827-28) depicts the disdainful figure of Sardanapalus who, upon being told that his palace is about to be overrun, gave orders for his concubines to be slain rather than for them to fall into the hands of the enemy. This cruel and despotic act and the events surrounding it are apocryphal and it comes as no surprise that Sardanapalus did not exist but was an invented figure that strategically transcends drama and history. In his notes to the works of Lord Byron, the literary scholar and poet Ernest Hartley Coleridge, grandson of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, wrote the following of Sardanapalus’s pedigree:

‘It is hardly necessary to remind the modern reader that the Sardanapalus of history is an unverified if not an unverifiable personage… The character which Ctesias [a Greek writer who popularized the theme] depicted or invented, an effeminate debauchee, sunk in luxury and sloth, who at the last was driven to take up arms, and, after a prolonged but ineffectual resistance, avoided capture by suicide, cannot be identified.'[17]

The absence of a verifiable antecedent here does not appear to have stopped the licentious, cruel and vengeful Arab becoming the default image of Arabness from Delacroix’s time up to and including Western media images and Hollywood-inspired imagery.[18] The visual constellation of these fears can be found in Ziad Abillama’s work Untitled (Arabes) (2011), a signpost in which it appears that all roads seem to lead to Arabs, a neo-conservative nightmare writ large on the ‘road map’ of the Middle East and beyond.

In 1926, there was an intriguing and well-documented court-case in the United States that was prompted by the photographer Edward Steichen’s attempt to import one of Constantin Brancusi’s Bird in Space sculptures, the latter being elongated abstractions of movement as much as they were three-dimensional representations of birds. At that time, there was no tax paid on art objects; however, the customs official did not view Brancusi’s abstracted bird figure as art and instead duly declared it an industrial item and thereafter placed a tax on it. In the subsequent trial, ‘Brancusi v. United States’ (New York, October 1927), a successful appeal was made against the US customs decision but not before two witnesses for the US government were called, one being the sculptor Robert Aitken. Arguing that he saw no beauty in the object nor did it resemble a bird to him, Aitken agreed with the defence that the object – having aroused no aesthetic feeling in him – could not be considered art. We have here, writ large in the annals of history, a conflict between an old aesthetic order wedded to naturalism and verisimilitude and, conversely, a modernist appeal to abstraction and a more subjective view of the world. The aesthetic here redistributes a sensible order – developing in turn a schism in the accepted ways of looking, seeing and thinking – and appeals to a new community of viewers and interlocutors.

I mention Brancusi’s work here for two reasons: one, it challenged a particular ‘distribution of the sensible’ and, secondly, his later masterpiece, Endless Column (1938), has become an iconic touchstone for many contemporary artists, not least Kader Attia who pays homage to it in La Colonne Sans Fin (2008), a seemingly never-ending column of megaphones reaching to the ceiling.[19] The formalism of Brancusi’s abstracted column, which was made as a memorial to the Romanian soldiers killed in the First World War, is here adapted to a more contemporary form of protest and memorialization. The visible here is made of the audible – or at least that which aids noise and sound – and the megaphone becomes a symbol of communication (for protestors) and coextensive repression (as used by the police). La Colonne Sans Fin is, in sum, responsive to the history of art as a practice and, coextensively, demonstrative forms of political engagement and control within and beyond the Middle East and North Africa.

On the face of it, Raafat Ishak’s Responses to an immigration request from one hundred and ninety four governments (2006-09), and Jananne Al-Ani’s Shadow Sites II (2011), would not appear to have much in common. However, both are engaged with detailing the politics of land ownership and the restrictions upon mobility that are placed on individuals. Ishak’s series of works stem from his collation of various responses from immigration offices the world over to requests for visas for Arabs to travel to those respective countries. These responses were subsequently trans-literated into Arabic and displayed as ciphers of sorts inasmuch as the literalized responses, when rendered into Arabic script, make very little sense to Arab speakers. For Ishak, the responses to immigration requests are also a form of seriality that recalls, in part, the uncompromising abstractions of Malevich who was a key reference in Ishak’s earlier work. Again, the history of art is brought to bear upon the less abstract and all too immediate reality of political if not cultural exclusion.

Whilst the recipients of such letters are left in a limbo-land of sorts awaiting some form of transition, in Jananne Al-Ani’s Shadow Sites II, a film made as part of a body of work called The Aesthetics of Disappearance: A Land Without People, this form of existence in limbo reaches a far more fatal conclusion. The desert in this film becomes a place of forensic examination – right down to the remotest detail and landmark – into notions such as ownership, inclusion and exclusion, atrocity and genocide, and the aesthetics of landscape. Through this work, the artist examines, to paraphrase the statement accompanying this piece, what happens to the evidence of atrocity and genocide and how it thereafter affects our understanding of the landscapes into which the bodies of victims disappear. The desert, a contested space that was often depicted in Orientalist painting of the late nineteenth century as an empty place – and therefore ripe for exploration and annexation – is here scoured for the very evidence of existence, even if it is in the form of remains, that contradicts any convenient notion of the desert as deserted or indeed neutral.

A magician on an impromptu stage stands in front of a makeshift curtain and singularly fails to execute, amongst others, a trick involving a reluctant chicken and its refusal to be hypnotized. This should be funny – and Yto Barrada’sThe Magician (2003) is indeed very funny. The recalcitrant chicken thwarts an elderly magician’s ability to complete a trick that he has probably failed to complete many times in the past. The camera’s presence has also no doubt produced a degree of hubris in this thwarted magician. There is a Beckettian quality to this film: a failure to transcend the physical reality of day-to-day slights and the humiliations brought upon one by age that becomes an end in itself, a form of heroic (if purgatorial) failure that resignedly commits, with each passing failure, to fail better. And yet there is an infectious promise in this short film, a sense that our willingness to suspend disbelief, the only pre-requisite of a magic trick, can be entertained again and again, despite the outcome. Perhaps this is the promise of visual culture: the transaction we enter into with the object or film or performance that promises nothing and yet holds out the promise of transcendence – or, more mundanely, an occasion for rethinking our world and its precariousness.

We may need to pause here and ask what the works in The Future of a Promise ultimately show us. They show us a region that is carefully policed and geographically contained and yet porous and fluid. In their demographic, they show us an art practice that is international and the product of sites of artistic production that stretch from Baghdad to Berlin, Cairo to Chicago, Tunis to Toronto, Alexandria to Allepo, Sharjah to Sydney. They show us a region not only with multiple artistic movements, but one without a coherent political standpoint or indeed a singular degree of religious affiliation. They show us a region in crisis over the very notion of culture and representation. They show us an artistic community realigned along the lines of an eminent diaspora, indigenous movements, and the development of an Arabic modernism, not to mention the influence of international art practices. They show us artistic practices recontextualized by globalization and the sinuous channels of capital. They figure alongside the role of social networking in the region – evident in Ahmed Mater’sAntenna (white) (2010), for example – and ways in which social networking groups have recently re-territorilialized the routes and means of communication. They reflect upon and anticipate the very social and public space needed to effect forms of civic engagement. None of which, I should add, necessarily makes these works political as such; rather, it makes them something far more radical: they are involved in a redistribution of the ‘sensible’ order and in that moment can redefine visual, social and individual forms of participation within and engagement with those orders. What these works shows us most clearly is a promise to engage the aesthetic as a potentially decisive tool in the realignment of how social orders understand the role and importance of culture in the development of civic society, public debate, social change, political equality and open discussion. They pursue a horizon of thought that opens up the potential of the aesthetic to anticipate the very parameters of civic society, its needs and its demands. For every artwork censored in the Middle East, for every show pulled, for every director summarily dismissed, the cost is immeasurably high: namely, the forfeiture of a civic and just society bolstered by freedom of expression and cultural debate – and no amount of billion-dollar window dressing and ill-defined, moral throat-clearing will compensate for that.

While not wanting to be too prescriptive, I would propose, by way of a conclusion, that the works on show here and in this catalogue hold out the promise of emancipation from the ill-conceived diktats of politics and the often ill-informed edicts of religion. In their potential to realign the distribution of signs, symbols and ways of looking and thinking (not to mention ways of being within a community), the practices represented in The Future of a Promise are always already political and capable of redefining roles and modes of engagement within a given socio-political order. And perhaps that is most evident when we ask the following: are visual artists such as those in The Future of A Promise showing us the beginning of the end of the term ‘Middle East’ as a shorthand to understanding a complex and diverse collection of countries. Are we looking at the emergence – through the prism of visual culture – of a ‘former’ Middle East as we did in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s and 1990s. And if we are experiencing the development of the former Middle East, how does that reflect upon our understanding of the so-called (former) West? What lies beyond the former Middle East if that is indeed what we are seeing currently emerging on the streets and in public spaces in the region? Are we looking at a new geographical, social, political, economic, religious and historical frame of reference under construction within the Middle East that necessitates the jettisoning of the very term? Can the aesthetic in this instance effect that most utopic and yet elusive of goals: the overthrow of one way of thinking for another. Only time will tell, but what remains beyond doubt is that nothing will ever be the same again in the Middle East, not least the very notion of the Middle East as a term of reference for those within and, crucially, beyond this amorphous, complex and far-from defined (if indeed definable) region. This is not, finally, about the promise of the future and the hubris of achievement as such; rather, this is about the precarious future of a promise that is made again and again in the aesthetic moment of artistic production and the networks of communication, debate and exchange that emanate from these activities.

[1] Jacques Rancière, ‘The Aesthetic Revolution and its Outcomes: Emplotments of Autonomy and Heteronomy,’ New Left Review (2002): 133.

[2] The arresting officer in question was one Fedya Hamdy who has reportedly since fled Sidi Bouzid.

[3] Samir Kassir’s Being Arab was first published in Paris in 2004, one year before his assassination in Beirut. To date, despite a tribunal having been set up to investigate the death of Samir Kassir, no one has been ever brought to trial.

[4] Raymond W. Baker et al., eds., Cultural Cleansing in Iraq: Why Museums Were Looted, Libraries Burned and Academics Murdered (London: Pluto Press, 2010).

[5] The targeted assassination of over 400 intellectuals, lawyers, artists and academics in Iraq following on from the coalition invasion of the country in 2003 remains one of the most shocking and sobering events in what has become an unmitigated disaster for the people of Iraq. Their deaths have not gone unnoticed, although nearly all remain un-prosecuted. Writing in Cultural Cleansing in Iraq, Dirk Adriaensens has detailed how the first wave of assassinations of academics coincided with the invasion in 2003. He also notes an SOS email sent by Iraqi scientists complaining that ‘American occupation forces were threatening their lives’. See: Dirk Adriaensens, ‘Killing the Intellectual Class: Academics as Targets’ in Cultural Cleansing in Iraq: Why Museums Were Looted, Libraries Burned and Academics Murdered (London: Pluto Press, 2010), 119. On the final pages of this volume the editors compiled an 18-page, small type list of the academics murdered in Iraq since 2003, which was in turn compiled from the Brussells Tribunal list which can be read at http://www.brussellstribunal.org/academicsList.htm. To read this document in full is to come away with a profound sense that whatever else is wrong with Iraq today, this list is testament to a gross and calculated failure to protect the Iraqi population in the present and, most damningly, provide for their futures in the form of education and culture. Generations, simply put, will be left bereft of the very things needed to build a nation.

[6] The scenario is, of course, more complex than I am allowing here. A fuller account of these debates would need to engage with, for one, Theodor Adorno’s writings on both aesthetics and politics. Whilst not wanting to simplify Adorno’s complex arguments on the nature of commitment and engagement (in the context of both aesthetics and politics), his skepticism towards politically committed art is instructive, critiquing as it does its tendency towards becoming agitprop. To paraphrase Adorno, such art tended to preach to the converted rather than transform social and political consciousness. The danger of politically committed and politically sanctioned art, in this context, was that it resulted in being neither interesting art nor, indeed, effective politics. None of which, however, should detract from Adorno’s belief that the aesthetic could critique social and political orders and thereafter offer a different way of imagining and engaging with the world. ‘Committed art in the proper sense,’ Adorno argued, ‘is not intended to generate ameliorative measures, legislative acts or practical institutions… but to work at the level of fundamental attitudes.’ See: Theodor Adorno, ‘Commitment’ inAesthetics and Politics (London: Verso, 2007), 180 and Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1970).

[7] See: Jacques Rancière, ‘The Politics of Aesthetics,’ 16 Beaver Group website www.16beavergroup.org/mtarchive/archives/001877print.html.

[8] See: Jacques Rancière’s, Aesthetics and its Discontents (Polity: Cambridge: Polity, 2009), 115.

[9] For Rancière, politics proper cannot emerge from our current ‘distribution of the sensible’ – in particular, neo-liberalism – insofar as the latter is based on consensus rather than dissensus or disagreement. It is in the moment of disagreement that the political subject proper emerges, not in the moment of consensus. It is precisely on the basis of disagreeing, for example, about the war in Iraq, and having debates that we enter into the realm of politics proper – which means, somewhat paradoxically, that we need to disagree if we want to agree with Rancière’s thesis. The policing of our political realm and the consensus around our current ‘distribution of the sensible’, nevertheless, continues to disavow and effectively depoliticize (and in some cases criminalize) the very realm of the political to the extent that protest and disagreement are rendered illegitimate responses. Who gets to say what, where and when is effectively proscribed by a consensus around the ‘distribution of the sensible’. For a further discussion on the role of dissensus and disagreement in politics, and his understanding of those terms, see: Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, trans. Julie Rose (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 21-42.

[10] It is crucial to note here that Rancière’s use of the term police or police order (la police or l’ordre policier) is not to be confused with the notion of the police force (la basse police) as a unit of the state. Rather, the term ‘police’ is used to define not repression as such but a ‘distribution of the sensible’ that distributes a population along lines of both inclusion and exclusion. These forms of partitioning and allocation of ‘bodies’ are based upon an individual’s predicated relationship to the ‘distribution of the sensible’, which is effectively a ‘system of co ordinates defining modes of being, doing, making, and communicating that establishes the border between the visible and the invisible, the audible and the inaudible, the sayable and the unsayable’. This is the order of consensus that Rancière interrogates throughout his work on both politics and aesthetics. In its abolition of dissensus and disagreement, consensus is the presupposition that the entire population, the multitude, the community, or the many, call it what you will,can be taken into account and incorporated into a political order that is policed through a distribution of the sensible or a ‘symbolic structuration’. This, again, is the logic of democracy as much as it is the logic of totalitarianism: everyone must have their place and be consigned (ifnot resigned) to their place. Consensus not only polices the political order but determines each individual’s role in relation to the social and political order. ‘Politics,’ Rancière argues, ‘exists wherever the count of parts and parties of society is disturbed by the inscription of a part of those who have no part. It begins when the equality of anyone and everyone is inscribed in the liberty of the people.’ See: Rancière, Dis-agreement (1999), 123, and Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum, 2004), 89.

[11] I have addressed this question at length elsewhere; see Anthony Downey, ‘The Production of Cultural Knowledge in the Middle East Today,’ in Art and Patronage in the Near and Middle East (London: Thames and Hudson, 2010), 10-15.

[12] There is a separate essay to be written on the role of censorship and self-censorship in the Middle East in relation to visual culture. At the time of writing, for example, the one-time Director of the Sharjah Biennial, Jack Persekian, who was also a Director of the Sharjah Art Foundation, had been summarily dismissed because of the apparent offence caused by the inclusion of Mustapha Benfodil’s Maportaliche/It Has No Importance (2011), the latter having since been removed from the 10th Sharjah Biennial.

[13] I would not want to give the impression here that culture is not regularly instrumentalized by neo-liberal, Western governments, nor the sense that it is not subject to censorship and the withdrawal of public monies and support. In the United Kingdom, for example, and with a very different emphasis but similar political inflection, artistic practices that support ideals such as inclusivity, consensus, voluntarism, multiculturalism and social cohesion – all of which underpin the moral communalism that is key to the ideology of neo-liberalism – have long been supported by the funding policies of Labour and Conservative governments alike. It would seem, moreover, that in light of recent cuts to the arts institutions in the United Kingdom we could be seeing the emergence of art forms geared specifically towards such funding.

[14] The subject of so-called democracy in the Middle East is an interesting one inasmuch as it brings about that bogeyman of Western neo-conservatism and liberalism alike: an Islamic democracy, the latter being seen as a contradiction rather than a reality for many. The subject deserves an essay in its own right – what, for one, do we mean by democracy and why exactly is it offered as a panacea for the Arab world when it patently fails to address inequalities and political forms of (non)representation in the so-called West? It is perhaps indicative that two essays could appear within four days of one another in London arguing, in the case of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, that the Arab world represented the future path that a more enlightened, egalitarian, form of democracy could take and, more conservatively, Niall Ferguson conversely arguing that democracy could not ‘catch on’ in the Arab world as it had no precedent there. See: Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, ‘Arabs are democracy’s new pioneers,’ The Guardian, 24 February 2011 and Niall Ferguson, Why Democracy will not Catch on in the Arab World,’ The Evening Standard, 28 February 2011.

[15] A new broom may indeed sweep away the old guard and it is all the more significant that this work was censored when recently shown at Art Dubai in 2011.

[16] In 2007, an American clothing store, Urban Outfitters, stopped selling keffiyehs after complaints from pro-Israeli activists, and thereafter issued a statement to the effect that the company had not intended ‘to imply any sympathy for or support of terrorists or terrorism’ in the act of selling keffiyehs. See: Michal Lando, ‘US chain pulls “anti-war” keffiyehs,’ The Jerusalem Post, 19 January 2007 http://fr.jpost.com.

[17] See: Ernest Hartley Coleridge, The Works of Lord Byron: Poetry, Volume V (London: John Murray, 1902), 4.

[18] I am reminded here of Jacqueline Salloum’s Planet of the Arabs (2005), in which we see snippets from a collection of Hollywood-inspired images representing the mendacious, cruel and violent Arab. This stock character ranges from the self-styled ululating terrorist overlord seeking retribution on an infidel Western culture to the buffoonish figure of the bumbling, oleaginous Arab. Taking her inspiration from Jack Shaheen’s 2001 book Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People, Salloum observed that from over 1,000 depictions of Arabs viewed in filmic form only a dozen were positive and 50 were what could be considered even-handed. Films with the most anti-Arab content, according to Shaheen’s account, include The Delta Force (1986), True Lies (1994) and Rules of Engagement (2000), all of which appear in Salloum’s film and all of which enjoyed extensive distribution to cinemas worldwide.

[19] Endless Column has been a point of reference for many artists, perhaps most notably Carl Andre who, rather than cutting into the work, arrived at the notion of the work itself being the cut into space.

Reference

Downey, Anthony. “Beyond the Former Middle East Aesthetics, Civil Society, and the Politics of Representation.” Ibraaz. Ibraaz, 1 June 2011.